Deriving The 2x2 Rotation Matrix

In linear algebra we learn that any linear transformation/map between finite-dimensional vector spaces can be represented as a matrix. Furthermore, it is easy to construct said matrix, as its columns are simply the linear map applied to the each basis vector. Specifically, for a map $T : \mathbb{R}^m \to \mathbb{R}^n$, there exists a matrix $M$ such that $Tv = Mv$ for all $v \in \mathbb{R}^m$. Let $e_1, \dotsc, e_m$ be the basis of $\mathbb{R}^m$, then,

$$ M = \begin{pmatrix} Te_1, \dotsc, Te_m \end{pmatrix} \iff M_{ji} = (Te_i)_j. $$

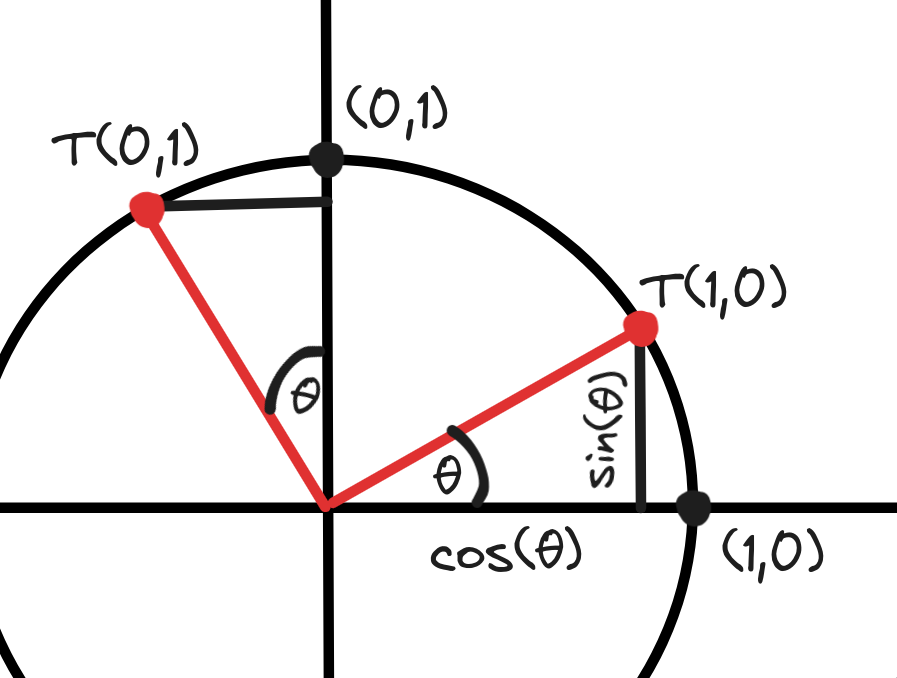

We can use this idea to derive the 2x2 rotation matrix. Let us imagine the linear map $T : \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R}^2$ that rotates a vector by $\theta$ degrees. Now, consider the value of $Te_1 = T(1,0)$. We can form a right triangle where the adjacent and opposite sides correspond with the X and Y positions of the rotated point $Te_1$ respectively. It is simple trigonometry then to find the length of the sides of the triangle given that the hypotenuse has length 1.

Now, since the X adjacent side is $\cos \theta$ and the Y opposite side is $\sin \theta$, we have the value of $Te_1$ as,

$$ T(1,0) = (\cos \theta, \sin \theta). $$

The same idea applies to the basis vector $e_2 = (0,1)$ where we construct a right triangle and find the length of its sides. However, the adjacent side corresponds with the Y value and the opposite side with the X value this time. Also, the X value is negated, since it's in quadrant II. Thus, we have $Te_2$ as,

$$ T(0,1) = (- \sin \theta, \cos \theta). $$

Finally, we can construct the 2x2 rotation matrix.

$$ R(\theta) = \begin{pmatrix} T(1,0), T(0,1) \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{pmatrix}. $$

In quantum computing you learn that the 2x2 rotation matrix is unitary, meaning that the matrix's transpose is equal to its inverse, or in other words, $M^TM = I$. These unitary matrices, as well as possessing other nice properties, have $|\det M| = 1$. Therefore, we can check that the rotation matrix we derived is valid by ensuring its determinant is 1. And a trick to memorize the 2x2 rotation matrix: The derivative of each row's first column is equal to its second.

$$ \begin{aligned} \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}x} \cos x &= - \sin x \\ \frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}x} \sin x &= \cos x \end{aligned} $$

P.S. You could probably derive the 3x3 rotation matrix in a simliar manner by applying this idea 3 different times on 3 different linear maps that rotate $\mathbb{R}^3$ vectors in the 3 ways to rotate in 3d space: yaw, pitch, and roll. We can then multiply these 3 matrices together to find the general 3d rotation matrix.